A Stroll Through Colonial Era

…Thus Began My Stroll Through Colonial Era.

A stroll through colonial era, just happened to me while searching some old boxes carrying land papers of my ancestors. And I stumbled upon some clues that drifted me to the corridors of colonial era – that was here to stay in Indian subcontinent and East Asia for almost 200 years, and was to touch the life of people of this part of world, in a big way.

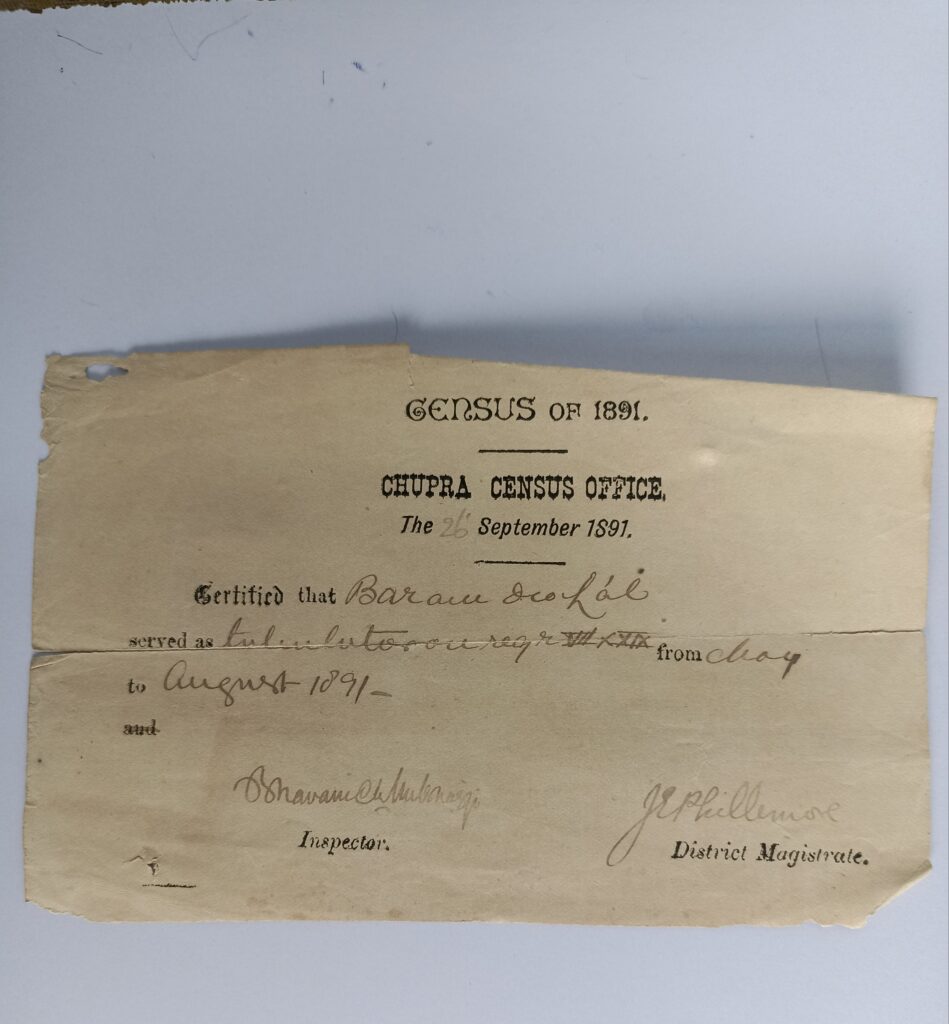

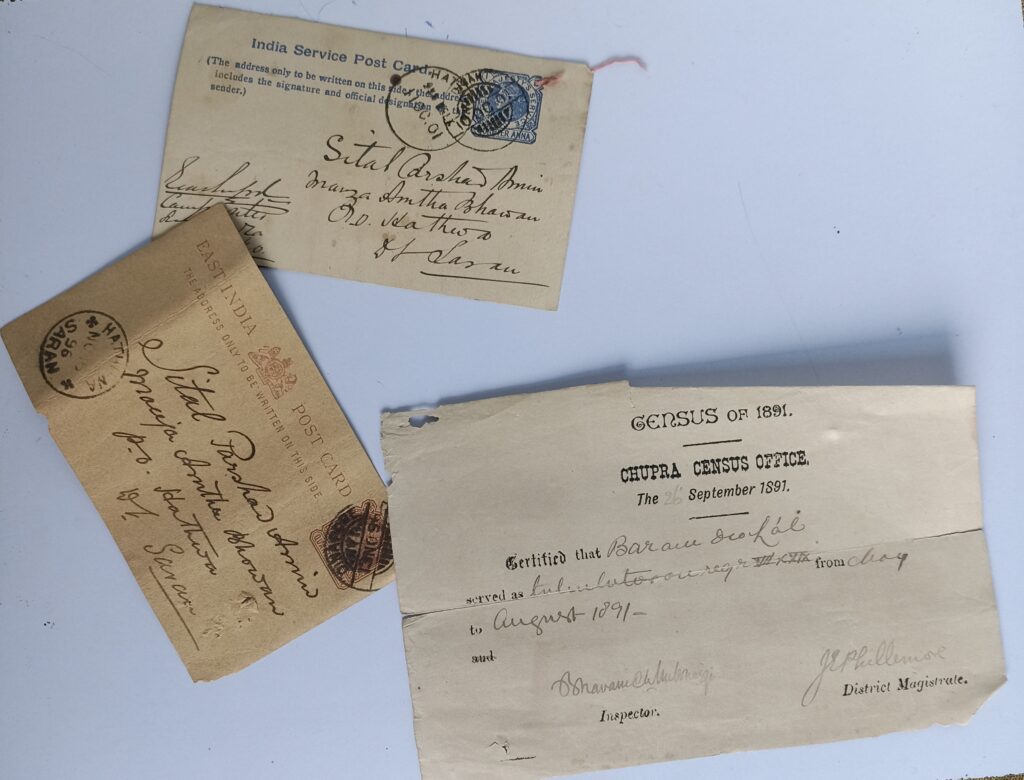

In the process, I found a partially decayed piece of paper. Actually this rubbed and worn out piece of paper turned out to be a certificate that belonged to the father of my great-great -grandfather; suggesting that he had worked as tabulator during 1891 Census of India in Amtha Bhuvan Mauza of Chupra district in State of Bihar in N. India. This worn out and dull looking paper inspired in me a reflection of hard work of my this ancestor which he would have done for his family.

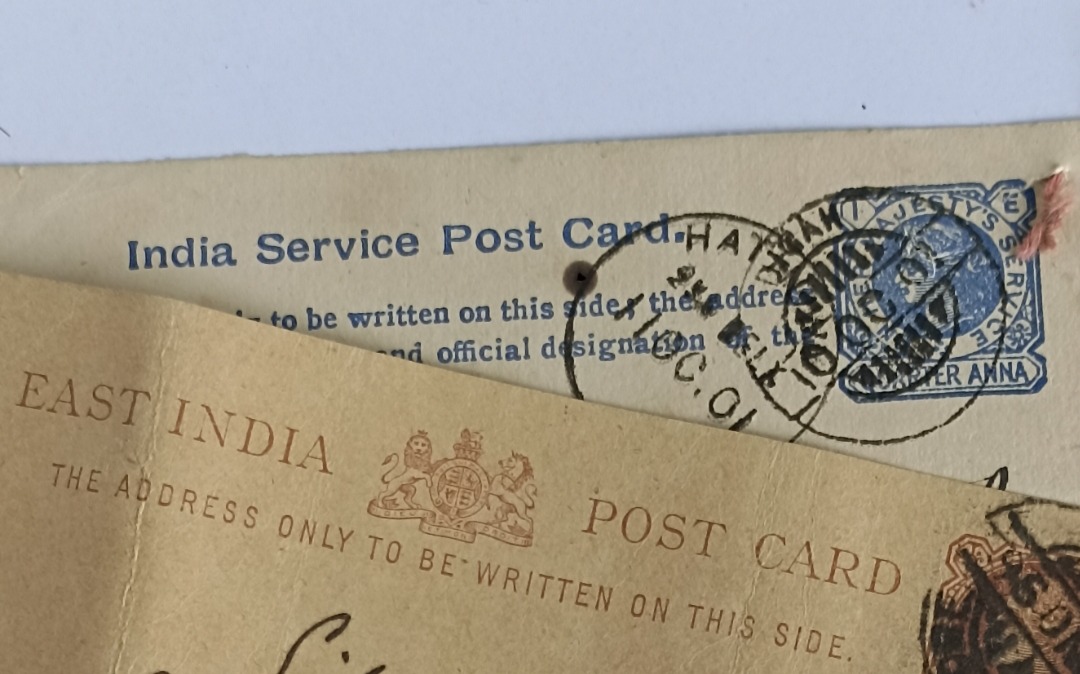

I held this decayed certificate in my hand affectionately and firmly, with utmost surprise, staring at each letter printed on it. It was colonial era, our ancestors had been turned into subjects of Her Majesty – reigning us from thousands of miles away in England!

Further surfaced some strange postcards, which showed the address of Sital Prasad – my great-great-grandfather. His name on this postcard was appended with a word ‘Amin’, which meant land surveyor, perhaps first non farm job activity in my family ! I was so touched and excited to discover this piece of information about my ancestor. I lost my patience and hurriedly shared this information with my family members at once.

The postage stamp and the emblem of the East India Posts on this postcard filled in me the echo of Atlantic sea waves hitting the shores of British Isles – the land of British East India Company, the land of Industrial Revolution and the land of Her Majesty !

Why During 17th – 18th Century, British Individuals Were So Interested to Come to India and East Asia?

In fact for quite some time a question constantly chased me that what was the lure , the attraction; that drew many British individuals to work in distant lands of India and East Asia during 17th – 18th century; leaving their food, flavor, family, relations, emotions, shores, lands, climate and all that nostalgia behind ?

Though our Western readers may understand it better, but, to many Asians and Indians, it is like a puzzle to understand why a British individual or other Europeans were so much interested to travel to the distant lands of East Asia and India even if it meant facing :

- A harsh tropical climate,

- Deadly diseases like Malaria and Dysentery,

- Long voyages with threats of Scurvy, and,

- Separation from family and British society.

So why did they still come ?

Rush to India – What Were The Reasons Behind?

Stories of India’s Richness.

India, particularly in 18th century, was a land of enormous commercial opportunity due to its vast agricultural and mineral base, and rich human resource. Works of its weavers, and craftsmen produced a range of goods that commanded a good price abroad.

Merchants and East India Company representatives to Mughal Courts were awestruck to see the wealth of Mughal Empire and regional rulers, and imagined the vast profits they could make through trade in spices, textiles, saltpeter, Indigo, and opium.

Many employees of East India Company returned to Britain amassing enormous wealth in India. Their extravagant lifestyles back home surprised their fellow citizens and earned them the name ‘Nabobs’. They became stuff of legend in Britain.

Rigid Class System in Britain

Many British individuals were second or third sons of aristocratic or middle class families. As per laws of inheritance in Britain, only eldest son was the favoured most. Younger siblings often had to find careers elsewhere. Also, in these societies of 18th century Britain, certain jobs were often seen as beneath their status. Jobs and economic activities like – manual trades, shop-keeping, or physical labour were socially unacceptable. In a situation like this; the East India Company (EIC) offered them a way to earn prestige and wealth, that was almost impossible for them in the prevailing rigid class system in Britain in those times.

Interestingly enough, it is personally very surprising for me when I draw parallels between my present native society here in North Indian state of Bihar and the then societies of aristocratic or gentry families in Britain. Until very recently, such psychology related to job preference played at full, among landed class of Bihar and U.P. causing a great difficulty to youths, in earning a socially acceptable livelihood at their native place.

Anyway, the rigid social code in 17th-19th century Britain; meant that an ambitious younger son couldn’t start a business to rise in wealth. Even commerce was often looked down upon by landed elite!

Thus many second and third sons sought fortune in the colonies, through –

- holding civil or military positions in East India Company (EIC),

- acquiring roles in Plantation or management in the Caribbean or Americas, and,

- getting administrative posts in newly acquired territories.

To add more to your surprise, even if a younger sibling made money abroad, integrating back into Britain’s elite could be a tricky exercise. colonial wealth was also often seen less pure than landed wealth ! So some returned officers from colonies were rich, but socially sidelined, unless they bought estates in Britain and married into established families!

You can realise all these things fairly happening in those times through following examples of many British individuals who came here in India, worked here for East India Company, found their fortune on Indian soil and returned back to their homes in Britain –

Robert Clive (1725-74) was born into a respectable but financially strained gentry family in Shropshire. He had limited prospects in Britain. Even jobs in military and law required funds and connections, which he lacked.

He came to India as a writer (Junior Clerk) for East India Company (EIC). Through military and political maneuvers – notably Battle of Palassey- he amassed wealth estimated at over 1,80,000 pounds (Tens of millions today) and returned home as a powerful though controversial figure. He also received Jagirs of lands around Calcutta.

Warren Hastings also belonged to financially struggling family. As a younger son, his inheritance was negligible. Thanks to rigid class system of Britain in 17th to 19th century ! He came to Bengal as a clerk for the East India Company (EIC) and rose through ranks to become the first Governor General of India.

Warren Hastings used his Indian career to secure wealth and marry into a respectable circle. Interestingly, he still faced prejudice from parts of British aristocracy as a ‘Nabob’ – a derogatory term for colonials who returned rich !

Similarly, Sir David Ochterlony (1758-1825) born in Boston to a Scottish merchant family, served in Bengal army of East India Company (EIC), rose to be the resident of Delhi. He famously had multiple Indian wives and adopted aspects of Indo-Mughal Court culture.

Again, William Palmer of Hyderabad was son of an English officer and an Indian mother. But he was a younger son of his family, thus having no formal inheritance. Later he became a major land holder and a banker at Hyderabad; essentially functioning as Zamindar, lending money to local rulers and living in aristocratic style !

And to add some more interesting examples, we can talk about Thomas Munro (1761-1827), second son of Glasgow merchant. He also didn’t have any family inheritance. In India, he joined Madras army of East India Company (EIC), played a major role in consolidating British control in South India and later became Governor General of Madras.

Also, Francis Skyes(1732-1804) was a younger son of a modest Yorkshire family. He made fortune as the company’s resident at Murshidabad. He acquired extensive zamindari rights in Bengal, used his wealth to buy estates in Yorkshire and entered parliament of Britain.

Many Scottish and East India Company (EIC) officers acquired zamindari rights in Bengal (ex- John Grant), and Bihar (ex- Edward Shore) after 1765, when company took over the Diwani rights (i.e. revenue collection rights) from Mughal Emperor.

Even many lower company officials, especially those in ports like Madras, Bombay and Calcutta, engaged in private trade such as shipping goods between Indian ports and South East Asia or China.

In some cases, some East India Company (EIC) officers even became moneylenders or even zamindars (Landlords) by exploiting the provisions of Permanent Settlement Act and grabbing land from Indian elites. They even lent money to Indian princes at high interest rates, and then used defaults as pretexts to for military intervention or annexation.

Final Words…

Actually, East India Company (EIC) offered ways to second and third sons of aristocratic or middle class families of England and Scotland, to leapfrog the British social bottlenecks, by making fortunes in India’s revenue system.

It has been rightly said, ”When England’s drawing rooms were closed to younger sons, the open plains of Bengal became their boardroom”.

Dear Readers…

Dear readers, hopefully along with me, you also must have come out with a convincing viewpoint about this puzzle that why British individuals were so much interested in coming to India and East Asia during 17th-18th century. You can write me in comment box below, your own views on this topic. It was a nice journey with you. Thank You.